Achalasia Overview

Achalasia is an uncommon swallowing disorder that affects about 1 in every 100,000 people. The major symptom of achalasia is usually difficulty with swallowing. Most people are diagnosed between the ages of 25 and 60 years. Although the condition cannot be cured, the symptoms can usually be controlled with treatment.

Achalasia Cause

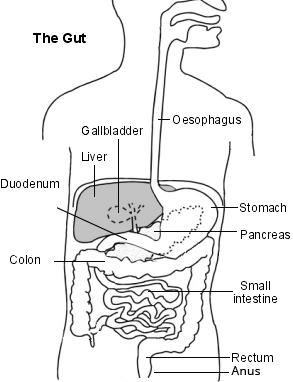

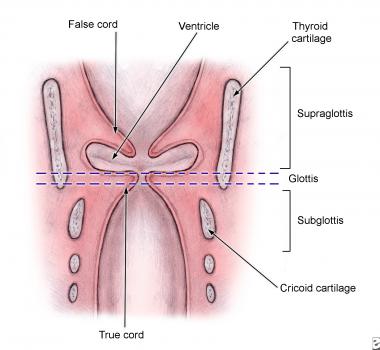

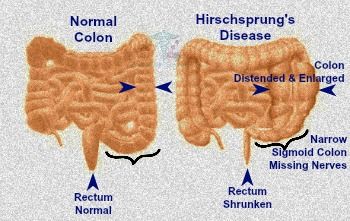

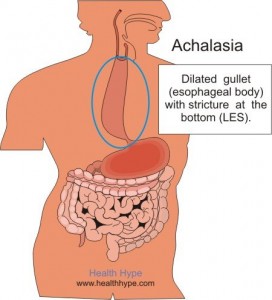

In achalasia, nerve cells in the esophagus (the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach) degenerate for reasons that are not known. The loss of nerve cells in the esophagus causes two major problems that interfere with swallowing.

In achalasia, nerve cells in the esophagus (the tube that carries food from the mouth to the stomach) degenerate for reasons that are not known. The loss of nerve cells in the esophagus causes two major problems that interfere with swallowing.

1/ The muscles that line the esophagus do not contract normally, so that swallowed food is not propelled through the esophagus and into the stomach properly.

2/ The lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a band of muscle that encircles the lower portion of the esophagus, does not function correctly.

3/ Normally, the LES relaxes when we swallow to allow swallowed food to enter the stomach. When the food has moved through the esophagus into the stomach, the LES muscle contracts to squeeze the end of the esophagus closed, thus preventing the stomach contents from flowing backward (refluxing) into the esophagus.

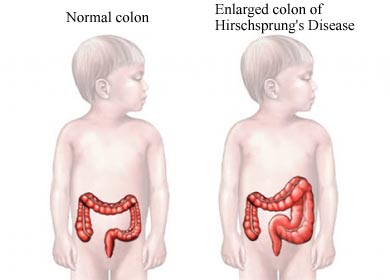

In people with achalasia, the LES fails to relax normally with swallowing. Instead, the LES muscle continues to squeeze the end of the esophagus, creating a barrier that prevents food and liquids from passing into the stomach. Over time, the esophagus above the persistently contracted LES dilates, and large volumes of food and saliva can accumulate in the dilated esophagus.

the esophagus, creating a barrier that prevents food and liquids from passing into the stomach. Over time, the esophagus above the persistently contracted LES dilates, and large volumes of food and saliva can accumulate in the dilated esophagus.

Achalasia Symptoms

The most common symptom of achalasia is difficulty swallowing. Patients often experience the sensation that swallowed material, both solids and liquids, gets stuck in the chest. This problem often begins slowly and progresses gradually. Many people do not seek help until symptoms are advanced. Some people compensate by eating more slowly and by using maneuvers, such as lifting the neck or throwing the shoulders back, to improve emptying of the esophagus.

Other symptoms can include chest pain, regurgitation of swallowed food and liquid, heartburn, difficulty burping, a sensation of fullness or a lump in the throat, hiccups, and weight loss.

Achalasia Diagnosis

Achalasia may be suspected based upon symptoms, but tests are needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Chest x-rays — A chest x-ray may reveal a dilated esophagus and absence of air in the stomach. However, a chest x-ray is not adequate for a diagnosis of achalasia and further testing is required.

Barium swallow test — The barium swallow test is a common screening test for achalasia. The test involves swallowing a chalky-tasting, thick mixture of barium while x-rays are taken. The barium shows the outline of the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Characteristic findings of achalasia on barium swallow include a persistently narrowed region at the end of the esophagus (the LES), with a dilated esophagus above the narrowed region. The barium swallow may also show spastic contractions in the esophagus above the LES, a condition called “vigorous achalasia”.

Esophageal manometry (also called esophageal motility study) — Manometry is a test that measures changes in pressures within the esophagus that are caused by the contraction of the muscles that line the esophagus. The test involves the passage of a thin tube through the mouth or nose into the esophagus. The tube is lined by numerous pressure sensors that convey pressures within the esophagus to a device that records those pressures. Patients are usually instructed to have nothing to eat or drink for eight hours before the test, and they are given sips of water to swallow while the tube is in place.

Manometry is almost always used to confirm the diagnosis of achalasia. The test typically reveals three abnormalities in people with achalasia: high pressure in the LES at rest, failure of the LES to relax after swallowing, and an absence of useful (peristaltic) contractions in the lower esophagus. The last two features are the most important and are required to make the diagnosis of achalasia.

Manometry is almost always used to confirm the diagnosis of achalasia. The test typically reveals three abnormalities in people with achalasia: high pressure in the LES at rest, failure of the LES to relax after swallowing, and an absence of useful (peristaltic) contractions in the lower esophagus. The last two features are the most important and are required to make the diagnosis of achalasia.

Endoscopy — Endoscopy allows the physician to see the inside of the esophagus, LES, and stomach using a thin, lighted, flexible tube. Most patients are given sedatives during the endoscopy procedure. This test is usually recommended for people with suspected achalasia and is especially useful for detecting other conditions that can mimic achalasia such as cancer of the upper portion of the stomach.

http://www.uptodate.com/contents/achalasia-beyond-the-basics